Subcapsular Hepatic Hematoma after Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Article information

Abstract

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is an important life-saving procedure in emergency care. However, CPR is associated with various complications. A 41-year-old man was admitted to the intensive care unit after CPR. A sudden decrease in the blood pressure and hematocrit level was recorded. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a large subcapsular hematoma in the left lobe of the liver. With conservative treatment, the hematoma reduced in size, but it was later managed with percutaneous drainage. The patient recovered and was discharged. We obtained a favorable outcome with conservative, nonsurgical treatment. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma is a potential life-threatening complication that should be considered in CPR survivors.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is an important, life-saving, emergency care procedure. CPR comprises chest compressions and artificial ventilation; during the former, the lower half of the sternum should be depressed to approximately one-third of the chest cavitary depth in each compression.

Complications of CPR include lung injuries (e.g., pneumothorax), rib fractures and contusion, damage to abdominal organs, and chest and/or abdominal pain.1–3 However, damage to abdominal organs is a rare complication of CPR. Here, we report a case of subcapsular hepatic hematoma, a rare complication of CPR.4–6

CASE

A 41-year-old man was hospitalized with a complaint of muscle weakness that was diagnosed as Guillain–Barres syndrome and appropriately treated. The patient experienced a sudden in-hospital cardiac arrest, was resuscitated, and there was return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after 5 minutes of CPR. Subsequently, the patient was admitted in the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Following ROSC, the blood pressure (BP) and heart rate were 105/84 mmHg and 129 beats/min, respectively. The patient was intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed the preserved left ventricular function without regional wall motion abnormality. The laboratory tests after CPR showed a white blood cell count of 15.14 × 109/L (neutrophils 70.4%), a hemoglobin level of 15.6 g/dL, a platelet count of 282 × 103/μL, an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 66 U/L, an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 115 U/L, a blood urea nitrogen level (BUN) of 37.0 mg/dL, pH 7.43, a partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 40 mmHg, a partial pressure of oxygen of 75 mmHg, a bicarbonate concentration of 26.4 mmol/L, and an oxygen saturation of 95.3%. Serum creatinine, albumin, and cardiac enzyme levels; partial thromboplastin time; and prothrombin time were all within normal limits.

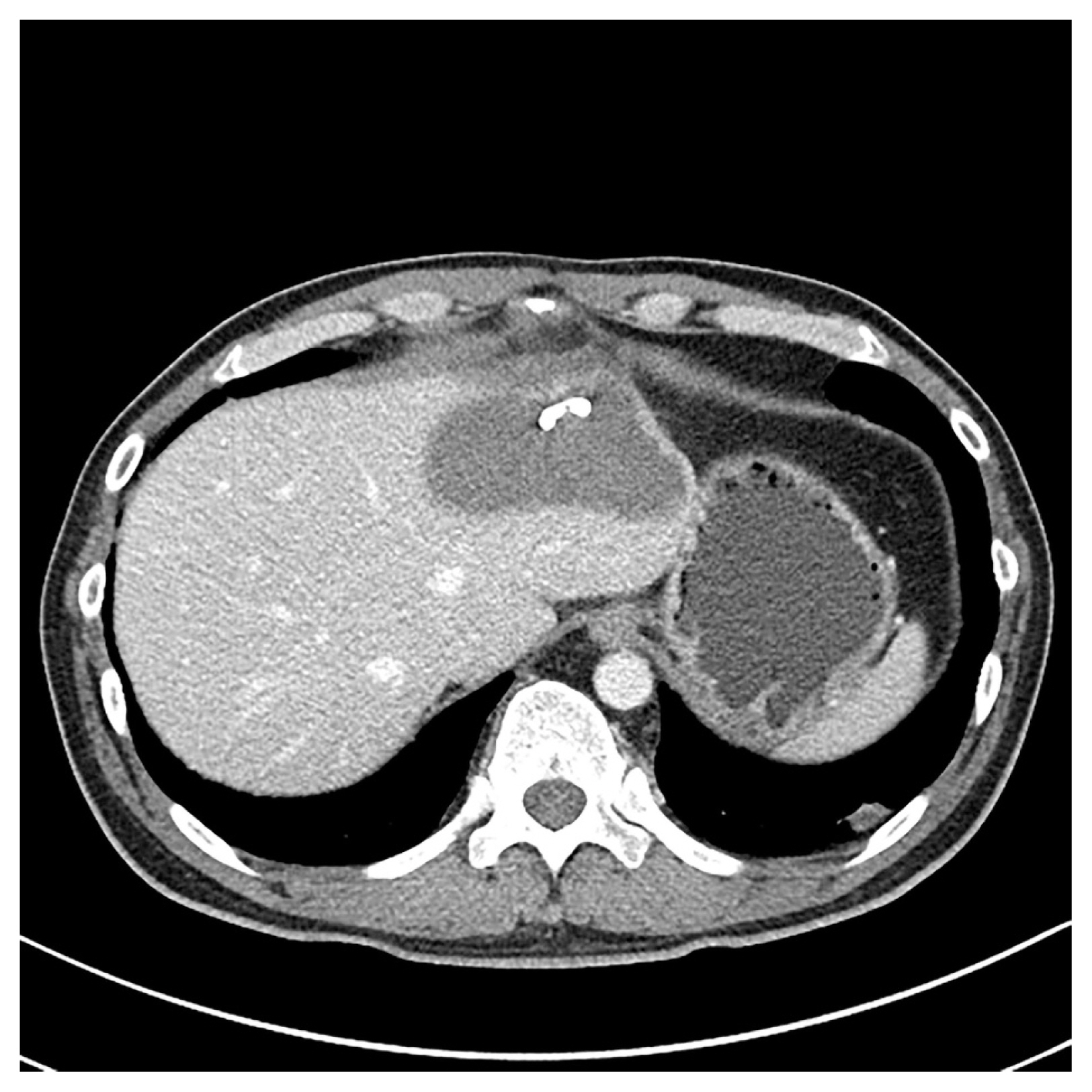

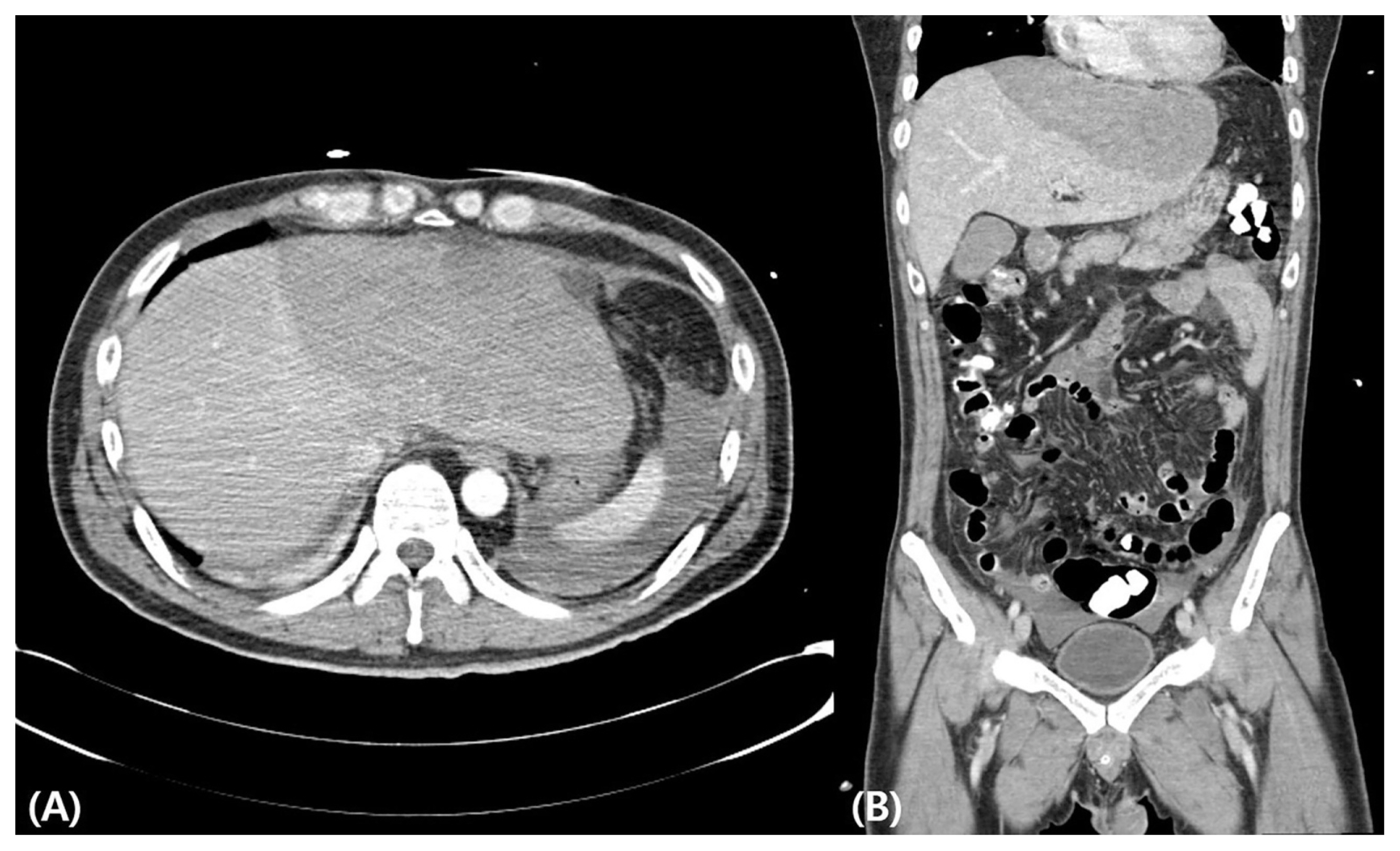

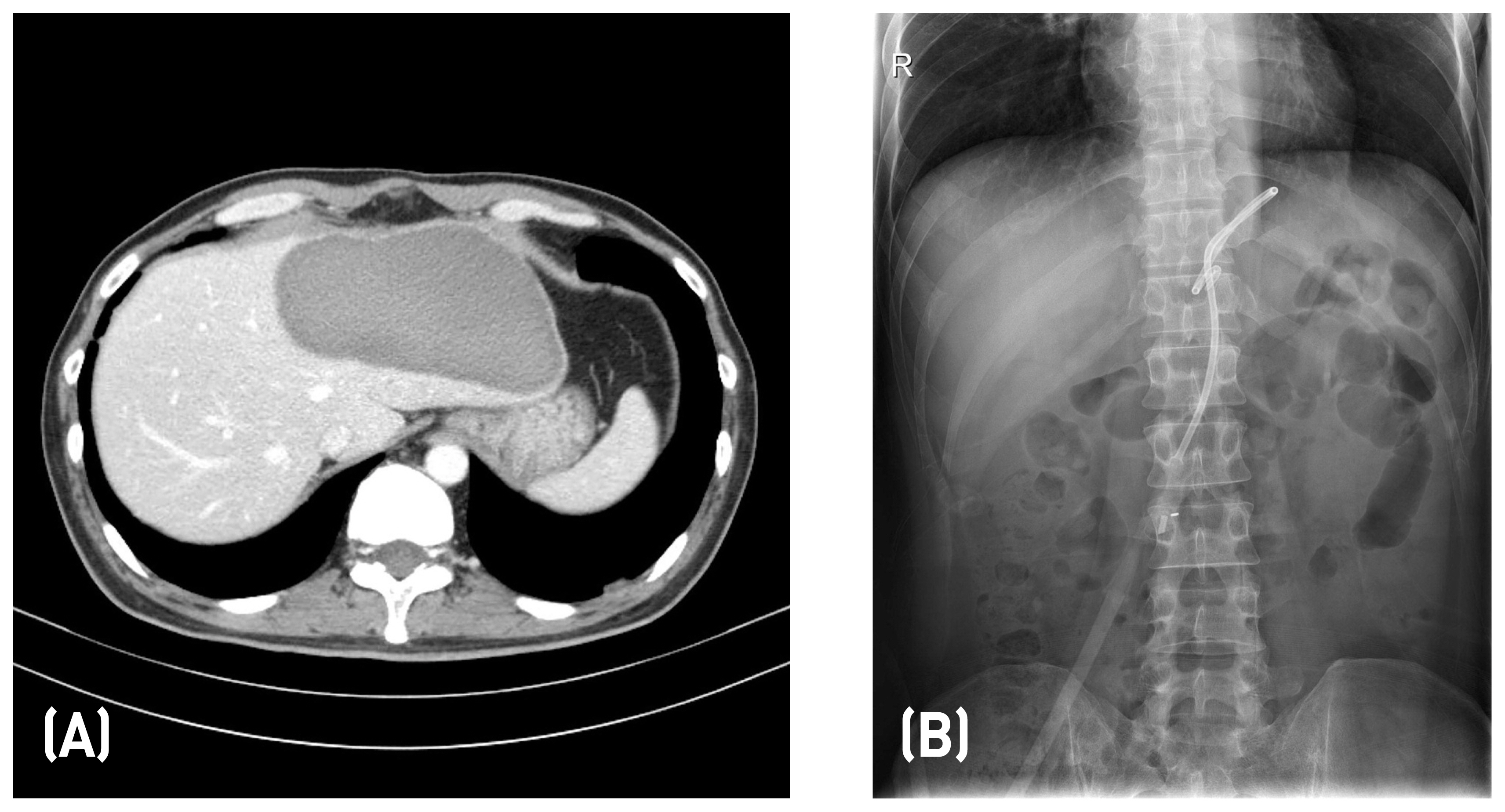

On the third day in the ICU, the patient’s BP decreased to 87/64 mmHg, and follow-up laboratory tests showed a rapid reduction in the hemoglobin level (7.7 g/dL). Esophagoduodenoscopy did not reveal any active upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Hence, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed to identify the source of bleeding, which showed a large subcapsular hematoma (17.8 × 7.9 cm2) in the left lobe of the liver (Fig. 1). We initially undertook a blood transfusion and conservative, nonsurgical treatment approach and the patient recovered slowly. The hemoglobin level returned to the normal range. There was no increase in the size of the hematoma on follow-up CT (Fig. 2A). In consultation with the surgical team, we inserted a percutaneous drain into the hematoma 1 month after the bleeding was detected (Fig. 2B). After 1 month of PCD insertion, the follow-up CT showed a decrease in hematoma (Fig. 3). Therefore, PCD was removed 1 month after PCD insertion. Subsequently, the patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged.

Abdominal computed tomography showing a large subscapular hematoma (17.8 × 7.9 cm2) in the left lobe of the liver (A) and small, diluted hemoperitoneum extending to the perisplenic space, mesenteric, and bilateral paracolic gutter and into the pelvic cavity

(A) Follow-up abdominal computed tomography showing subtle decrease in the size of the subscapular hepatic hematoma (14.9 cm from 17.8 cm, in axial size) in the left lobe of the liver and no abnormal fluid collection, (B) Abdominal X-ray showing percutaneous insertion of an abdominal drainage catheter into the subcapsular hepatic hematoma

DISCUSSION

This case report describes a male patient with a subcapsular hepatic hematoma that developed after CPR. For effective CPR, the sternum needs to be depressed 4–5 cm in each compression. Rib fractures are the commonest complication of CPR and can occur in up to 50% of patients.1–3 Other chest complications include hemothorax, pneumothorax, hemopericardium, and sternal fracture. Intra-abdominal injuries including hepatic, splenic, or intestinal trauma and retroperitoneal hematoma have been reported after CPR.4,6–8 However, liver injury occurs rarely (0.6%–2%) and is usually associated with anticoagulation therapy.4,9

In our case, a subcapsular hepatic hematoma of the left lobe was noted. Liver injury most often occurs in the left lobe during CPR. The most important contributory factor for this is the close anatomical relationship of the left lobe of the liver with lower part of the sternum.6,10 Hemodynamic instability is a leading symptom of intra-abdominal bleeding. Measuring the hematocrit level might be a useful test in the post-resuscitation phase.9 When a subcapsular hematoma of the liver is diagnosed, it is important to perform continuous imaging tests and blood tests such as hemoglobin in determining conservative or surgical treatment and to monitor whether the hematoma does not progress.11 In general, subcapsular hematoma that does not rupture is treated conservatively, and the prognosis is good. In spite of symptomatic treatment, selective embolization of the hepatic artery branch may be considered to control hematoma enlarged or continued bleeding, and octreotide may be used to reduce bleeding.12 Surgical treatment is recommended for subcapsular hematoma rupture or imminent rupture. Typically, 75% of patients die when the hematoma is ruptured. However, CPR-induced liver injury is usually addressed with conservative management and embolization.5,6,13 About 7 – 20% of the patients with complications died from the cause of CPCR (eg, cardiac arrest, pulmonary theomboembolism, etc.), but one of them died due to massive bleeding.4–6,8–10,13–17 Most of the surviving patients recovered without any specific liver-related complications.4–6,8–10,13–17 In our patient, the vital signs were stable after transfusion, and conservative treatment was recommended on surgical consultation.

Compression during CPR is emphasized with the revision in the resuscitation guideline and is the essential component of basic life support.18 Frequent interruption of chest compressions does not provide circulatory support for more than half of the resuscitation effort. Such interruptions can be a major cause of the consistent poor results, which manifest as a heart attack.19 Compression should remain as undisturbed as possible during CPR. With the focus on compression, unusual complications such as a subcapsular hepatic hematoma have been discovered. 5,17 To reduce the occurrence of such complications, it is important to apply compression in the right position with the correct pressure.

In Korea, Wi et al. reported a case of liver laceration with hemoperitoneum after CPR.6 A 72-year-old female patient developed severe hemoperitoneum associated with liver injury after CPR and underwent emergency embolization, but she died.6 In addition, in Korea, there have been cases of spontaneous liver injury occurring after delivery,20 after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography,21 during hemodialysis,22 liver abscess,23 idiopathic24 and recovery with conservative treatment in most cases. However, in our case, conservative treatment alone recovered liver injury following CPR.

In patients with a sudden drop in hematocrit level and blood pressure after CPR, it is important to evaluate the hemorrhagic foci. Despite liver injury being an uncommon finding in such an evaluation, it is important to consider it in the differential diagnosis to facilitate correct diagnosis and treatment, which will improve the patient’s prognosis.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.