Epidemiology and Causation

Article information

Abstract

In medicine and public health areas, it is essential for researchers and clinicians to investigate causal relationships dealing with the terms of cause, causation and causality. In treating a patient, the treatment will be given based on the assumption that that treatment will cause an improvement or cure of the patient. For diagnosis, we need a causation concept to associate diseases with etiologic factors such as genetic, environmental, occupational and other components. The prevention and intervention of a disease involve the selecting process of probable causal factors too.

The causal problem is one of main issues in philosophy since ancient Greek. Aristotle theorized material, formal, efficient, and formal causes. Francis Bacon and Descartes mainly used induction and deduction, respectively. Hume denied the capacity of inductive methodologies to find truth. Among philosophers of science, the debates whether we can find objective truth or not will be continued. This causation can be two subsets, ontological and epistemological (or methodological). Traditional philosophical approaches mainly focus on ontological problems, such as what is causation?; are there causal laws? In general, scientific or epidemiological approaches are dealing with the epistemological dimension, i.e, causation criteria; test for a causal hypothesis.

For clinicians and researchers in medical and public health, it would be a good chance to review and re-think the notions of cause, causation and causality. Also there will be helpful understanding of more detail informations about the methodology such as causal inference, Hill’s criteria and Rothman’s causal pie model.

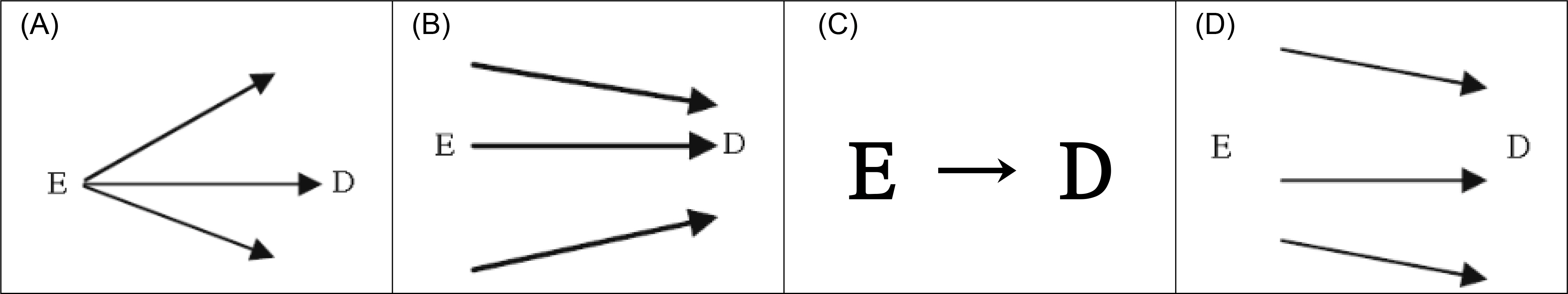

(A) A necessary cause, (B) A sufficient cause, (C) A necessary and sufficient cause, (D) Most of causes.

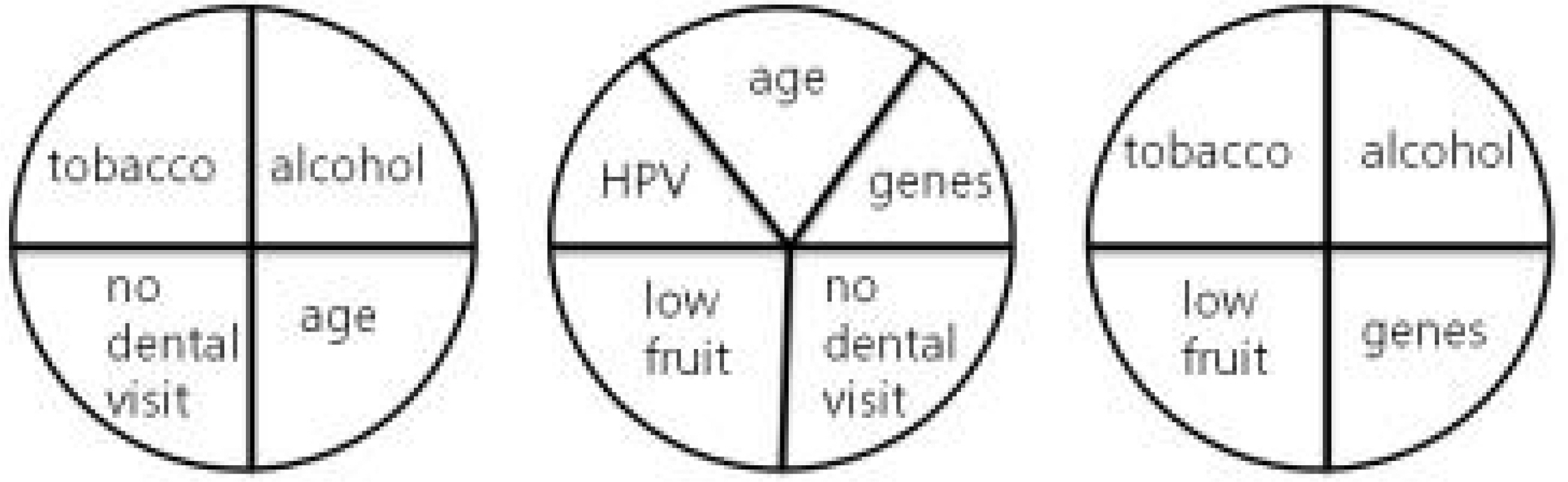

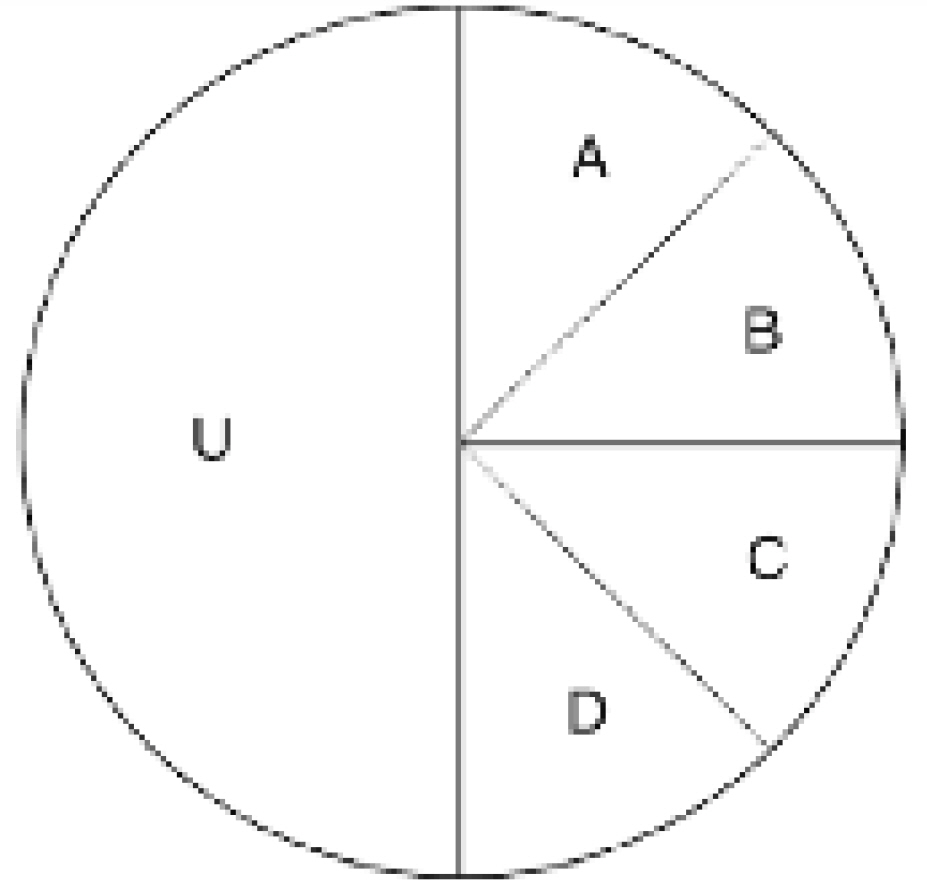

Depiction of the constellation of component causes that constitute a sufficient cause, and U represents all of the other unspecified event, conditions.