Disseminated Staphylococcus aureus infection and acute bacterial pericarditis: a case report

Article information

Abstract

We experienced a case of disseminated Staphylococcus aureus infection with bacterial pericarditis that progressed to septic shock and multiorgan failure despite pericardiocentesis and surgical removal of the original abscess with intensive antibiotic therapy. We report this case because of the patient’s very rare and remarkable echocardiographic findings and highly turbid pericardial effusion.

Introduction

Acute pericarditis typically has a good prognosis when it is idiopathic or is caused by a viral infection. Purulent pericarditis is rare and accounts for less than 1% of all pericarditis [1,2]; the mortality rate is very high if left untreated [3]. In present case, when pericarditis results from bacterial infection and proceeds to septic shock, its prognosis becomes unexpectedly poor.

Case

Ethical statements: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kosin University Gospel Hospital (2022-03-025), and informed consent was waived due to retrospective study.

A 46-year-old male patient was referred to Kosin University Gospel Hospital (KUGH) from a local medical center for ongoing chest pain and dyspnea for the past 3 days, with suspicion of acute pericarditis. He had undergone a nerve block procedure due to back pain 3 weeks before and otherwise had no underlying disease.

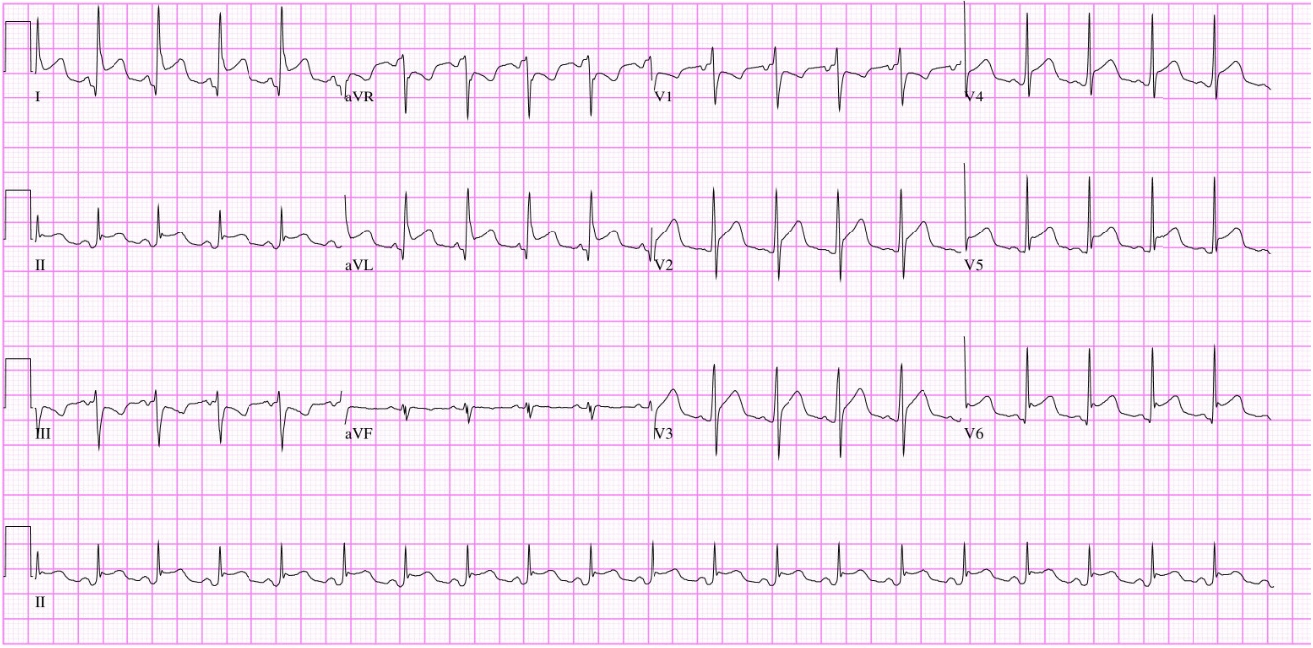

At the emergency department, the patient had the following vital signs: blood pressure, 110/89 mmHg; heart rate, 128 beats/min; body temperature, 39º; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min, and an O2 saturation of 90% in ambient air. The initial electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia and ST elevations at the limb lead and precordial lead (Fig. 1). Chest X-ray indicated severe cardiomegaly. The patient’s laboratory tests were also abnormal, with 24.34×103/μL white blood cells (normal range: 4.0×103/μL–10.6×103//μL), a hypersensitive C-reactive protein of 27.9 mg/dL (normal range: 0–0.75 mg/dL), and a procalcitonin level of 1.788 ng/mL (normal range: 0–0.65 ng/mL). He also had an NT-Pro BNP of 659.8 pg/mL, which was over the upper normal limit. A coronavirus disease 2019 polymerase chain reaction test was negative.

Electrocardiography. The initial electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia and ST elevations at the limb lead and precordial lead.

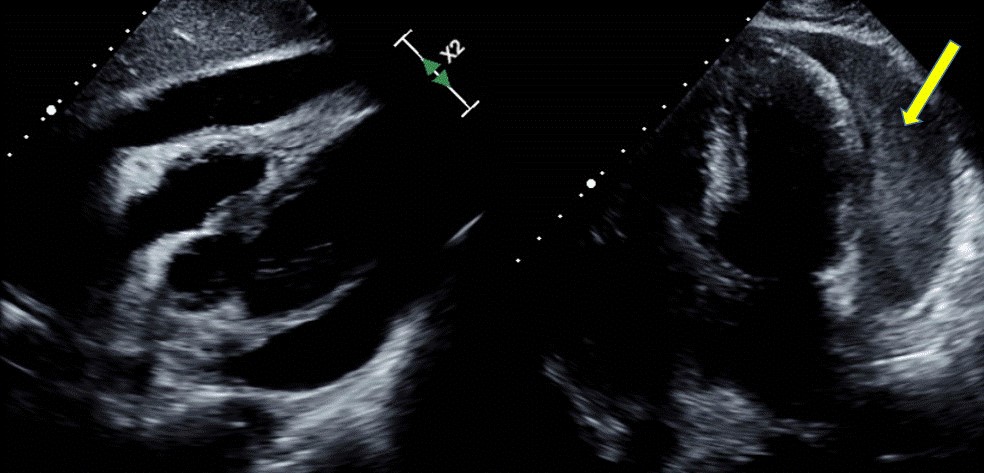

Coronary arteriography had been performed at the local medical center and showed no coronary artery lesion. At KUGH, chest computed tomography with enhancement was performed, and a greater than moderate amount of pericardial effusion was noted. There was no pulmonary thromboembolism or pneumonia. Echocardiogram revealed a large amount of pericardial effusion without cardiac tamponade physiology, and the pericardial effusion on the left side had high echogenicity like as significant spontaneous echo contrast (Fig. 2). Pericardiocentesis was carried out immediately, and a very turbid, brown-colored effusion was drained (Fig. 3). Acute pericarditis was suspected; to find the source of infection, spinal magnetic resonance imaging was performed based on the patient’s history of a recent lumbar spine nerve block procedure and persistent tenderness around the lumbar spine. There was abscess formation at the epidural space and the retrodural space of the lumbar spine. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was isolated from cultures of both blood and pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram revealed a large amount of pericardial effusion, and the left side (yellow arrow) had high echogenicity resembling significant spontaneous echo contrast.

The patient’s clinical course showed no improvement after pericardiocentesis. Because of the possibility of disease progression to septic shock, a surgical procedure was carried out to remove the lumbar spine abscess, which was considered the infection source. A large amount of whitish-colored abscess material was removed, from which MRSA was isolated. After surgery, the patient was medically managed with intravenous antibiotics, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), hemodynamic support with vasoactive drugs, and mechanical ventilation. Nevertheless, uncontrolled sepsis proceeded to septic shock and then multiorgan failure. The patient expired on hospital day 21.

Discussion

In our case, when pericarditis results from bacterial infection and proceeds to sepsis and septic shock, its prognosis becomes unexpectedly poor. Suspicion of purulent pericarditis is an indication for urgent pericardiocentesis, which is diagnostic [4]. The most common infectious strains are staphylococci, streptococci, and pneumococci [3]. In purulent pericarditis, intravenous antimicrobial therapy should be started empirically until the microbiological results are available. In addition, aggressive management is needed, and drainage is crucial [5].

This was a severe case of acute pericarditis with disseminated S. aureus infection that proceeded to septic shock and multiorgan failure. The patient had a poor response to aggressive treatment of immediate pericardiocentesis, surgical removal, intravenous antibiotics, and CRRT. It may have been important to consider surgical removal of the pericardial abscess. However, since metabolic acidosis was not corrected, lumbar spine surgery was performed while maintaining CRRT, the patient's risk of surgery was too high to remove the pericardial abscess, so it could not be performed. The patient experienced symptoms for about 3 weeks after an lumbar spine procedure, during which the condition progressed to systemic sepsis. The delay in treatment is thought to be the most important cause of death.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JHH. Data curation: SHB, SHL, JYC. Investigation: BJK. Methodology: BJK. Resources: BJK. Supervision: JHH. Validation: BJK. Visualization: SJK, SII, HSK. Writing - original draft: BJK, SHB. Writing - review & editing: BJK, JHH. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.