Alcohol-related liver disease and liver transplantation

Article information

Abstract

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) has become the major cause of liver transplantation (LT) in Korea, and is currently the most common cause of LT in Europe and the United States. Although, ALD is one of the most common indications for LT, it is traditionally not considered as an option for patients with ALD due to organ shortages and concerns about relapse. To select patients with terminal liver disease due to ALD for transplants, most LT centers in the United States and European countries require a 6-month sober period before transplantation. However, Korea has a different social and cultural background than Western countries, and most organ transplants are made from living donors, who account for approximately twice as many procedures as deceased donors. Most LT centers in Korea do not require a specific period of sobriety before transplantation in patients with ALD. As per the literature, 8%–20% of patients resume alcohol consumption 1 year after LT, and this proportion increases to 30%–40% at 5 years post-LT, among which 10%–15% of patients resume heavy drinking. According to previous studies, the risk factors for alcohol relapse after LT are as follows: young age, poor familial and social support, family history of alcohol use disorder, previous history of alcohol-related treatment, shorter abstinence before LT, smoking, psychiatric disorders, irregular follow-up, and unemployment. Recognition of the risk factors, early detection of alcohol consumption after LT, and regular follow-up by a multidisciplinary team are important for improving the short- and long-term outcomes of LT patients with ALD.

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is the only available treatment option for survival in the cases of liver failure in patients with terminal disease. Repeated and continuous alcohol consumption has been identified as a substantial risk factor for chronic liver disease, and the net effect of alcohol consumption on health is estimated to account for approximately 3.8% of deaths worldwide [1,2].

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) has become the major cause of LT in Korea, and is currently the most common cause of LT in Europe and the United States (US). One of the biggest reasons for the increase in LT in ALD is the decrease in chronic hepatitis B patients in Korea, which is related to the decrease in LT patients with hepatitis C owing to the use of direct-acting agents in Western countries. However, the decrease in hepatitis B and C, which have been the main indications for LT, cannot fully explain the increase in LT in patients with ALD. LT for ALD has several ethical dilemmas. Alcoholism has recently been considered as a chronic and relapsing-remitting neurological disease with a definite biological background, and the change in attitude towards LT in ALD is also one of the reasons why LT has become the main treatment for ALD [3-5].

ALD is one of the major causes of chronic liver disease, accounting for approximately 48% of cirrhosis-related deaths in the US. Persistent alcohol consumption is the main cause of alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH), cirrhosis, and liver cancer [6].

Despite the environmental and genetic factors associated with alcohol use disorder (AUD), ALD is still regarded as self-harm by some transplant doctors. Transplantation access for LT candidates with ALD is still marginal. Of the potential candidates with ALD, only approximately 5% to 10% of the patients have been selected for LT [7,8].

These results could may at least partially explain why transplant waitlist registrants with ALD present have high Model for End-stage Liver Disease scores, and why a higher proportion of waitlist registrants have severe decompensated complications compared with other patients on the waiting list.

Current status of LT for ALD

According to the United Network for Organ Sharing report, up to 2015, the LT waitlist and LT surgeries for patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related chronic liver disease, the first indication for LT, accounted for 33% and 28%, respectively. Since 2016, ALD (30%) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (21%) have accounted for more than half of the total waiting list, and LT surgeries due to ALD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis have surpassed HCV. In Europe, LT for alcoholic cirrhosis (AC) increased abruptly from approximately 35% in 1988–1995 to 45% in 1996–2005. Since 2019, AC has become the major cause of LT. Therefore, ALD has become the leading cause of LT in the US and Europe [9,10].

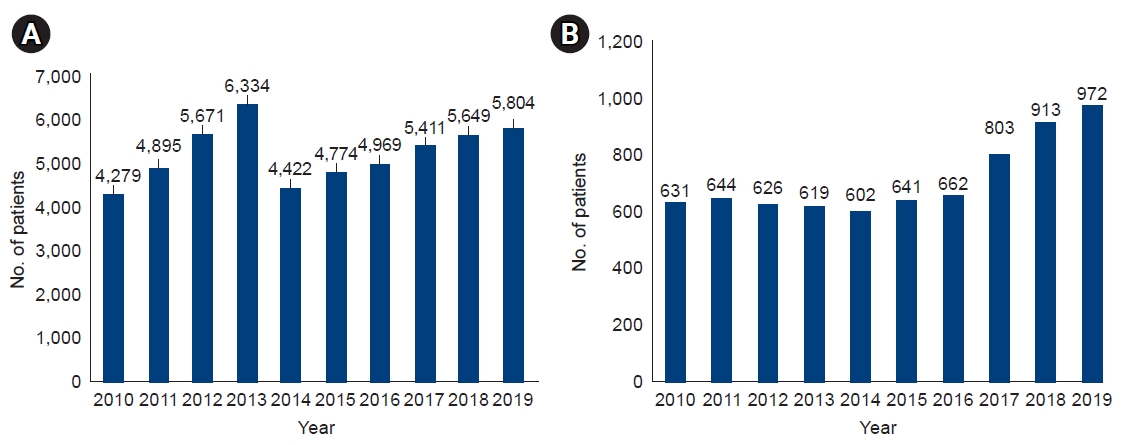

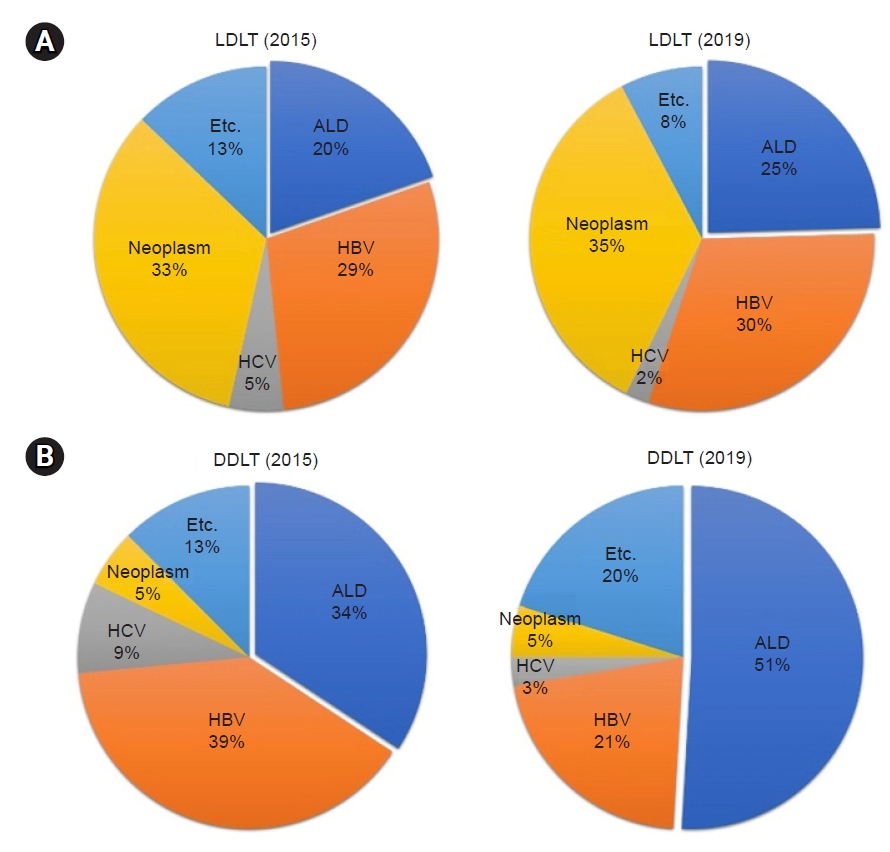

In Korea, the number of patients waiting for an LT increased from 4,279 in 2010 to 5,804 in 2019, and the number of deaths due to the unavailability of a liver for transplantation steadily increased from 631 in 2010 to 972 in 2019 (Fig. 1). Korea is an endemic region for hepatitis B virus (HBV), with approximately 5% of the general population being HBV carriers; however, it has been controlled by a national vaccination program for all neonates in Korea since 1995 and a national screening program for antiviral treatment. Thus, the patients who received liver grafts from deceased donors for ALD has increased sharply, from 34% in 2015 to 51% in 2019, while the number of patients undergoing living donor LT has increased gradually, from 20% in 2015 to 25% in 2019. Similar to Western countries, ALD has pushed HBV as the second causative disease and has become the primary etiology of LT in Korea (Fig. 2) [3,11].

Changes of etiology for liver disease in liver transplantation in Korea. (A) Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). (B) Deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT). HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease. Data are from Korean Network for Organ Sharing [3].

Alcohol-related liver disease

ALD represents a spectrum of liver damage due to repeated and continuous alcohol misuse, from alcoholic fatty liver to more advanced forms, including ASH, liver fibrosis, AC, and severe alcoholic hepatitis presenting with acute-on-chronic liver failure. ALD is one of the major causes of chronic liver disease worldwide, both by itself and as a contributor to the aggravation of chronic viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and other liver diseases [6].

In general, the risk of ALD increases based on the amount of alcohol intake (≥30 g/day). The minimum amount required to cause cirrhosis is approximate ≥30 g/day in men and ≥20 g/day in women. In most studies, alcohol intake of 40–80 g/day increases the risk of liver damage. People who consume more than 60 g of alcohol per day develop steatosis, and some people with steatosis develop ASH, of which 10% to 20% eventually develop cirrhosis. In addition, both genetic and non-genetic factors can influence both individual susceptibility and the clinical course of ALD [12-14].

Disease spectrum

1. Fatty liver

Fatty liver is the first response to repeated alcohol misuse and is incarnated by the deposition of adipose tissue in the hepatocytes. Macrovesicular steatosis, with its characteristic foamy cytoplasmic appearance, is the early and most common observed pattern of alcohol-induced liver damage from alcohol. There are four major pathogenic factors as follows: (1) increased nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide synthesis caused by alcohol oxidation; (2) increased hepatic inundation of chylomicrons and free fatty acids; (3) ethanol-mediated blocking of adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase effect, which inhibits peroxisome proliferating-activated receptor α and stimulates sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c to increase adipogenesis and reduce lipolysis; (4) acetaldehyde-induced mitochondrial and microtubules damage, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidation, and very low-density lipoprotein accumulation, respectively [15-17].

2. Steatohepatitis

ASH is an advanced form of hepatic injury in patients with repeated alcohol misuse and can present as an acute-on-chronic hepatic failure, resulting in rapid deterioration of liver function, and increased mortality. Despite the aggressive therapy, approximately 30% to 50% of patients with severe ASH eventually die [18]. ASH is pathologically determined as the existence of steatosis, hepatocyte swelling, and the inflammatory infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. ASH is a clinical syndrome that refers to the recent onset of symptoms, such as ascites and/or jaundice in patients with persistent alcohol intake. Although clinical symptoms may appear abruptly, the term "acute" is not recommended, as it is an aggravation of the underlying ALD and usually follows a chronic long course. However, the exact prevalence of ASH remains unknown. According to a study that used the National Inpatient Database in the US, ASH contributed to 0.8% of all hospitalizations in the US, with approximately 325,000 hospitalizations in 2010. The population burden of AC is underestimated and is not clearly known, and there is a higher probability of AC in patients hospitalized for alcohol-related problems. The clinical features of ASH are characterized by severe jaundice and are associated with the risk other related other complications. ASH can occur at any stage of liver disease and up to 80% of patients with severe ASH presenting with underlying AC. Patients with severe ASH are hospitalized for treatment, which can also lead to complications such as hepatic failure and sepsis. Alcoholic fatty livers can cause repeated parenchymal inflammation and cellular damage, which increase the risk of progression to fibrosis and cirrhosis. Various factors can contribute to ASH development, which are as follows: (1) toxic effects of acetaldehyde; (2) lipid peroxidation due to reactive oxygen species production and Deoxyribonucleic acid adduct formation; (3) pro-inflammatory cytokines levels. Repeated alcohol misuse can also result in changes in the colonic microbiota and increased intestinal permeability, resulting in increased serum lipopolysaccharides levels, which induce inflammatory actions in hepatic Kupffer cells [19-21].

3. Cirrhosis

AC is an advanced, chronic form of ALD. Progressive alcoholic steatosis can result in septal fibrosis and cirrhosis, which are characterized by the development of extensive scarring (fibrosis) and regenerative nodules. The development of fibrosis is a major change in ALD as it is an essential prerequisite for the exacerbation of cirrhosis. The progression of fibrosis varies according to the histological lesions of ALD. As with other etiologies, patients with AC are susceptible to decompensation-related complications due to high portal pressure and hepatic failure and are at risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma [12,22]. A study of patients diagnosed with AC showed that the 1- and 5-year mortality rates were approximately 30% and 60%, respectively. Hepatic encephalopathy is considered the most dangerous sign and symptoms among the complications that define hepatic decompensation [23].

Alcohol use disorder

AUD is the leading cause of cirrhosis in European countries and the US. AUD is a chronic medical condition defined as an unhealthy pattern of alcohol consumption. When alcohol is not consumed, it can cause clinically significant impairment that can include compulsive alcohol quest, positive reinforcement, and negative emotional states. These include alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, alcohol addiction, and a condition that some people colloquially call alcoholism [2,24].

AUD has become a significant public health concern over the past decade, and its prevalence has increased at an alarming rate. According to an epidemiological survey conducted in the US between April 2012 and June 2013, 12-month and lifetime prevalence rates of AUD were approximately 13% and 29%, respectively. The prevalence rate increased from 8.5% to 12.7% between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013, constituting an increase of approximately 50%. This increase was particularly prominent among minority-race groups, city dwellers, women, and low-income individuals. AUD affects 10% of the European population [2,25].

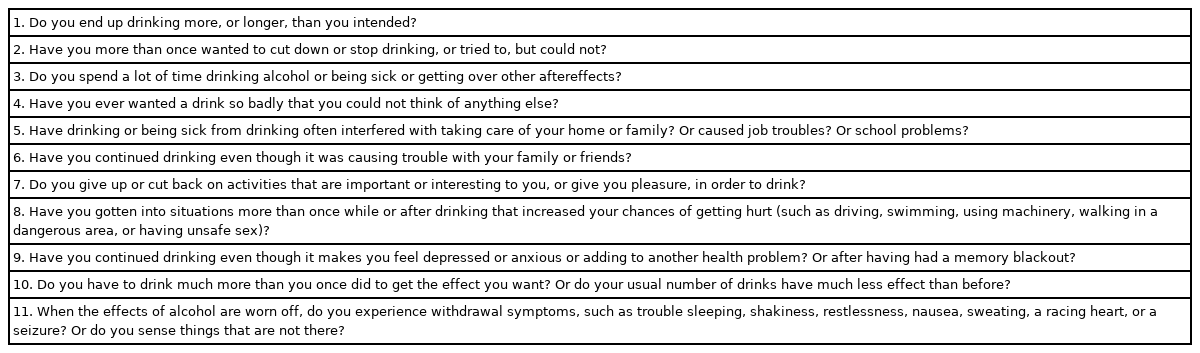

AUD diagnosis using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) requires at least two of the 11 criteria. According to the following DSM-5 criteria, the AUD is classified as follows according to the severity: mild, moderate, or severe (2–3, 4–5, or ≥6, respectively) (Table 1) [26-28]. Addiction specialists consider AUD as a chronic disorder of relapse and remission. For addiction experts, relapses in drinking should be defined by the amount and frequency of alcohol intake. However, most LT centers have an absolute view of alcoholic consumption and define any drinking as relapse [29-31].

Pre-LT management

Treating patients with AUD is extremely challenging both before and after LT. The most important and major treatment plan for patients who undergo LT after surgery is complete abstinence; if alcohol consumption continues even after medical or surgical treatment, the treatment effect is inevitably limited. If there is no improvement in liver function even after complete abstinence, and symptoms of decompensation persist, LT is the best treatment option.

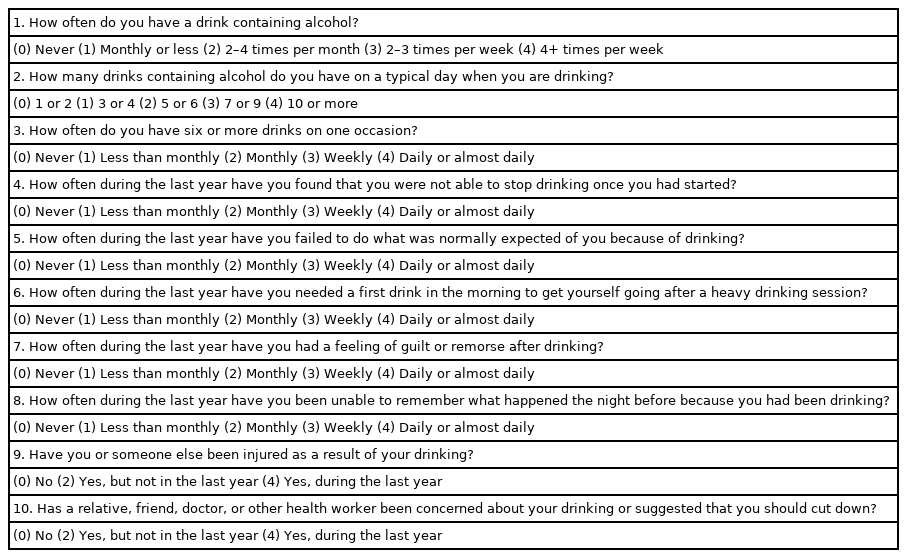

All patients preparing for LT should be screened for AUD before surgery, even if the reason for LT is not ALD. AS the role of the pre-LT assessment is to identify the best fit for transplantation, an initial recommendation may be that an individual needs treatment for addiction before a final decision is made. Establishing abstinence before LT is the most important starting point. The AUD identification test (AUDIT) comprises 10 questions with a scoring system. An AUDIT score of >8 is considered a positive screening test result indicative of the presence of AUD. A score of >20 indicates alcohol dependence, and the patient should be referred to an addiction specialist (Table 2) [28]. Patients with AUD often undergo LT evaluation after hepatic decompensation (i.e., ascites, variceal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy) or are managed palliatively without considering a transplant.

1. Behavioral therapy for pre-LT AUD

Behavioral therapy is the mainstay of AUD treatment in LT candidates and recipients. LT programs in many Western transplant centers require regular attendance at alcoholic anonymous meetings after completing behavioral therapy before being put on a waiting list.

2. Pharmacotherapy for pre-LT AUD

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has suggested the AUD treatment guidelines. This guideline describes several pharmacological agents, including naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, topiramate, and gabapentin. The APA recommends the administration of naltrexone or acamprosate to patients with moderate-to-severe AUD as the first-line treatment. Naltrexone blocks the effects of opioid receptors and suppresses alcohol intake and desire. Drug levels of naltrexone after administration are different in patients with compensated cirrhosis and those with decompensated cirrhosis; therefore, it is not recommended in the decompensated cirrhosis group with severe decompensated complications. Acamprosate has shown efficacy in treating AUD, especially for preventing alcohol relapse in previously sober patients. A study in patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class A or B liver cirrhosis showed safety outcomes and, although results in the severe cirrhosis group; however, studies on patients with CTP class C liver cirrhosis are limited. Disulfiram is an alcohol-insensitive drug that alters the patient's response to alcohol, resulting in a dispersant and loathe experience. Disulfiram has hepatotoxic effect; therefore, it is not recommended for use in patients with advanced liver disease. The APA also suggests that topiramate or gabapentin should be administered be as the second-line treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD. Topiramate is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anticonvulsant that works as a glutamate blocking agent in addition to gamma-aminobutyric acid agonistic effects. The APA recommended its use in cases of intolerance or suboptimal responses to first-line drugs (i.e., naltrexone and acamprosate). Although topiramate causes no direct hepatotoxicity, it exhibits indirect hepatotoxicity because it is metabolized by cytochrome P3A4. Therefore, it increases the levels of valproic acid and other anticonvulsants, which may cause hepatic injury. Gabapentin is in a class of anticonvulsant medication approved by the FDA for treating epilepsy and nerve pain. The APA recommends gabapentin for patients who show first-line treatment failure or cannot tolerate first-line treatment.

In the future, there may be more drugs related to the treatment of AUD. For example, a randomized controlled trial reported that varenicline, a drug for smoking cessation, reduced binge drinking and usual social alcohol drinking days, and increased smoking cessation compared to with a placebo.

LT for ALD

Although ALD is one of the most common causes of LT in the US and Europe, LT has traditionally been not considered as an option for patients with ALD due to organ shortage and concerns for relapse [10,25,32].

The survival rates of patients at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after LT for AC are reported to be 84%–89%, 78%–83%, 73%–79%, and 58%–73%, respectively. The overall survival rates were similar to those of LT in patients with HCV cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. However, the 10-year survival rate for patients with harmful drinking after LT is 45%–71%, compared with 75%–93% for patients who refrain from drinking or occasionally drink [10,33-37].

Grat et al. [37] reported that there was no difference in the overall survival rate at postoperative 5 years in patients with ALD who underwent LT; however, the survival rate deteriorated beyond the fifth year after transplantation in patients with ALD, and ALD was a risk factor.

Hong et al. [11] reported that the 1-year and 3-year overall survival rates of deceased donor LT (DDLT) for the patients with ALD and HBV were 90.7% and 82.1% in the HBV patients group and 92.1% and 82.3% in the ALD patients group, in Korea, respectively. They reported that there were no significant differences in the 1-year and 3-year overall survival rates between the two groups [11].

The improvement in survival rate after LT in patients with ALD patients differs according to the severity of liver disease, especially in severe AC with CTP grade C decompensated cirrhosis. CTP grade C patients who underwent LT showed significantly higher 1-year and 5-year survival rates compared with the control group; however, there was no significant increase in survival benefits for AC patients with CTP grade A or B compared with the control group [38,39].

Prevalence of alcohol relapse after LT

LT can cure liver disease, but not AUD. Therefore, the LT teams should be aware that patients who have undergone LT for ALD may experience alcohol relapse whenever after surgery. However, the precise proportion of patients with alcohol relapse after LT remains unknown. The prevalence of alcohol relapse varies from 10% to 90% in several studies due to differences in the definition of relapse and follow-up time after LT. As per literature, 8%–20% of patients resume alcohol consumption 1 year after LT, and it gradually increases to 30%–40% at 5 years post-LT. Studies estimate that up to 20%–50% of patients who undergo LT will be readmitted for alcohol-related problems within 5 years after LT, and approximately 10%–15% of the patients resume heavy alcohol consumption [14,29,40-43].

A meta-analysis showed an alcohol relapse and heavy alcohol relapse rate of 22% and 14%, respectively, at a mean follow-up of 24 months after LT. Studies have shown poor outcomes in patients with alcohol relapse after performing LT for ALD compared with patients with no or intermittent alcohol intake. A meta-analysis by Rustad et al. [44] showed that patients with alcohol relapse had a higher risk of steatohepatitis, rejection, or liver failure, and mortality. The results of this study highlight the importance of examining alcohol use after LT and identifying steps to avoid negative consequences [5,44,45].

Definition of alcohol relapse after LT

The reported definitions of alcohol relapse vary widely, from sobriety to alcohol-related consequences, such as hospital readmissions, or physical, social, and legal consequences. Failure of sobriety is the commonly used definition because it emphasizes the recommendation to abstain from alcohol completely; however, there is no evidence that mild relapses (occasional “slips,” less than once per month) have effects on graft or patient survival. The most effective methods for identifying alcohol relapse post-LT are the clinical interviews and the Alcohol Timeline Followback questionnaire; however, more research on the utility of combining several methods needs to be conducted [32,46].

Some experts stipulate relapse as four or more alcoholic drinks per day or 14 or more total drinks per week for at least 4 weeks [47,48]. Arab et al. [49] suggested a three-stage definition of alcohol relapse according to the relapse severity: (1) mild; (2) moderate (continuous and repeated drinking, at daily and weekly doses within the recommended standards of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism); and (3) severe (associated morbidity or mortality, which includes alcohol-induced hepatitis, pancreatitis, hepatic graft loss or other medical problems associated with alcohol recurrence). DiMartini et al. [50] suggested four patterns of alcohol consumption stage depending on the time of relapse, quantity, and duration as follows: (1) minimum drinking over a long period; (2) early relapse that progresses rapidly to moderate consumption; (3) early relapse that progresses to a repeated and continuous harmful drinking; (4) moderate drinking with a late start.

Many LT centers consider even a single drop of alcohol consumption after LT to be a relapse, and addiction experts do not support this definition. Data accumulated over the past decade show that reducing alcohol consumption, whether intoxicated or not, lowers overall morbidity, mortality, and health costs, and improves the psychosocial status. Alcoholism experts define AUD as a chronic disease that recurs with exacerbation and improvement, and the treatment focuses on changing it from severe to mild [51-53].

Unfortunately, there are few well-designed studies on interventions to improve outcomes in patients with ALD after LT, as the treatment goals of post-LT studies for ALD are still unclear. Mathurin and Lucey [54] proposed that, in order to achieve this goal, future studies should recalibrate the outcome goals of recipients with ALD as either abstinence (the ideal outcome) or low-risk drinking (acceptable outcome).

Six-month abstinence rule

A 6-month abstinence rule has been proposed because of organ shortages and concerns regarding sharing limited resources with patients with self-inflicted conditions who are at risk of alcohol relapse after LT. In this context, pre-LT alcohol abstinence is one of the hottest and most controversial issues. This rule has been a general requirement since 1997. During a national meeting for LT in ALD in 1997, and all transplant professionals agreed that abstinence from alcohol prior to LT is an important prerequisite for selecting patients for LT and most European and US programs require a definite period of abstinence lasting 6 months (the so-called 6-month abstinence rule) [40,55]. To identify patients with ALD who are eligible for LT, many transplant centers in Western countries require the 6-month rule to followed before transplantation can be considered. However, unlike the US and Europe, Korea has a different cultural and social background than Western countries, and most organ transplants are made from living donors, which is about twice that of deceased donors. Most transplant centers in Korea do not require a specific period of sobriety before LT either living donor LT or deceased donor LT for patients with ALD. In recent years, more patients with ALD have received transplants from deceased donors in Korea. Of the deceased liver donors in 2012, 18.7% were allocated to patients with ALD, and the proportion was 38.0% in 2017, without the requirement of any abstinence period [3,43].

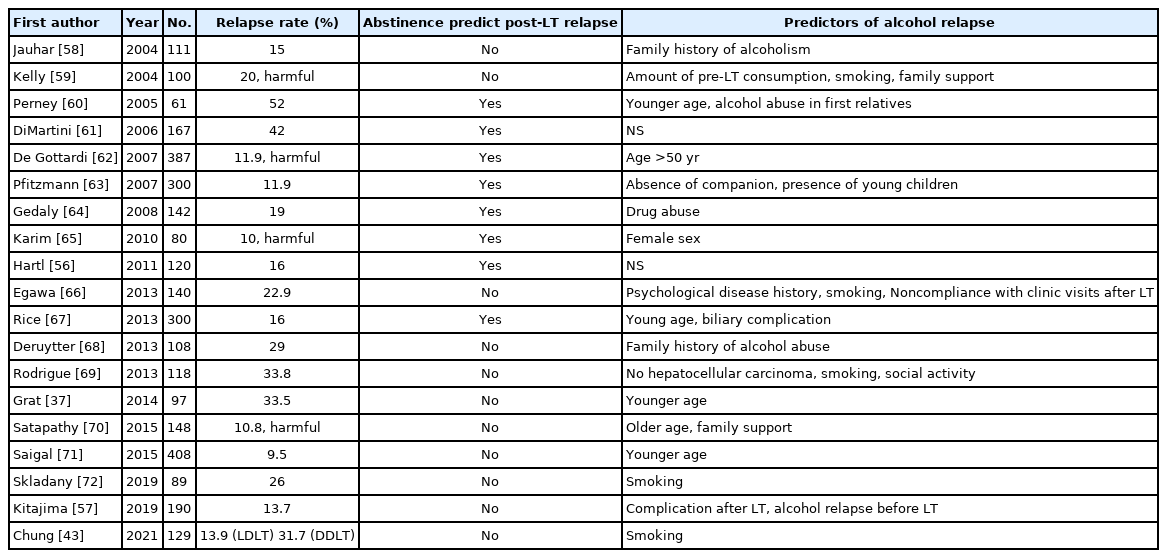

Although abstinence before transplantation is the most widely studied predictor, it has not been shown to be a significant predictor of recurrence after LT in many studies. Additionally, different cutoffs for pre-transplant abstinence (3 months and 1.5 years) have been found in various studies [56,57].

The 6-month abstinence rule serves two purposes. First, to give the patient time to demonstrate abstinence (which is thought to be predictive of abstinence after LT) and second, to give the patient an opportunity to recover through medical treatment after abstinence [73].

Risk factors for alcohol relapse after LT

Various predictors of recurrence after LT have been investigated. Many studies are retrospective and used different definitions of alcohol relapse after LT, making comparisons challenging (Table 3) [37,43,56-73]. Several studies have identified the associations between demographic and clinical factors and alcohol relapse after LT. According to the literature, the commonly reported risk factors in the several studies are poor social and familial support, young age, smoking, psychiatric disorder, family history of AUD, previous treatment history for AUD, short abstinence period before transplantation, irregular follow-up, divorce, separation by death, and unemployment [5,43,49,50,61,72,74].

Conclusions

It is a known fact that abstinence is a pivotal factor for improving the long-term prognosis in patients who have undergone LT for ALD, and alcohol relapse is the most serious problem for patients. Few prospective studies have been conducted to reduce recurrence after LT for ALD. It has been considered that continuous intervention before and after LT is extremely important, and this can be achieved by the accurate identification of risk factors for recurrence after LT. In this sense, the key to the main treatment of these patients is the role of the multidisciplinary ALD team before and after surgery. A multidisciplinary team approach in combination with biochemical screening, can identify early recurrence and improves post-LT survival in patients with ALD. Recognition of risk factors, early detection of relapse after LT, and regular follow-up by a multidisciplinary team are essential to improve the prognosis of LT patients with ALD.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

Musheer Shafqat and Young Il Choi are editorial board members of the journal but were not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: YIC. Data curation: YIC. Formal analysis: MS. Investigation: JHJ. Methodology: HHM. Project administration: DHS. Resources: DHS. Software: JHJ. Supervision: JHJ, HHM, DHS. Validation: DHS. Visualization: YIC. Writing - original draft: YIC. Writing - review & editing: MS. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.